The Woodworking Bench

I've been working on the KesterHouse renovation in one form or another for well over ten years now, and when ever I've had to do some special roof rafter cutting, custom framing joints, or finish carpentry work, I've somehow muddled through working on a pile of lumber with an old door on top, all stacked on a couple rickety plastic folding sawhorses. That's just silly. As I move forward with more interior work, I'm finding I really need to get myself a proper workbench so I can hold the stock I'm working — whether it's just to do some sanding and finish application, or for hand planing and working on various joints for finish trim. Wobbly stuff piled on sawhorses with clamps I always have to move as I work on each piece of stock just ain't makin' it anymore.

I suppose I could just screw down a nice solid-core door to a pair of sturdy wooden sawhorses and call it done, but come on — you know me better than that by now… I started thinking about what manner of bench to build after reading Christopher Schwarz's Workbenches a couple years ago, and followed that with The Workbench Design Book. Schwarz is a big fan of Roubo's massive bench that was described in his The Art of the Joiner, vol. I, published in 1769. Schwarz described and built Roubo's bench, refered to as the "French style", and also built a bench usually attributed to Peter Nicholson as the "English style" bench. The popularity of both bench types soared in the last few years, and there are many companies around now selling kits, plans, and fixtures for these centuries old bench designs (and some of them, while very nice, are incredibly expensive). Rather than spend thousands to buy a beautiful pre-made bench (that's going to end up in a plastic storage garage for at least a year), it's time I finally made myself a proper woodworking workbench.

Table of Contents

This joiner's bench page seems to be turning in to my joiner's bench book, so I've added this table of contents to help navigate to the various sections.

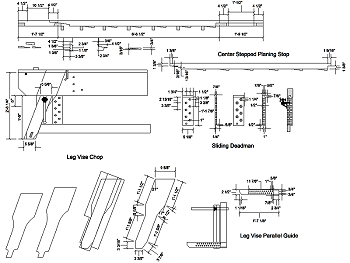

- Bench History & Design examines what I'm basing the bench design on, and ends with the initial plans for my design.

- Building the Joiner's Bench walks through each step of construction for the bench base, apron, and top.

- Stock Preparation: Selection of the materials and initial prep.

- Leg Cutting & Glue-up: Starting with the legs, the stock is cut and glued up for thickness.

- Leg Mortise & Tenon Work: Details the preparation of the two leg assemblies.

- Leg Unit Assembly & Drawboring: The leg assemblies are put together with drawboring.

- Base Stretcher Assembly & Bench Bolts: Tying the two leg assemblies together with the base stretchers.

- Top Stretcher Installation: The final piece of stock for the base is installed.

- Base Assembly & Workholding Hardware Installation: A few pieces of hardware are added to the base prior to finish application.

- Base Finish Prep & Application: The base is completed, edges dealt with, and finish applied.

- The Front Apron: Work begins on the apron with hole layout.

- More Front Apron Work: The apron backer board is screwed and glued into position.

- The Tail Vise Frame: Before moving to top assembly, the frame for the tail vise is built.

- The Tail Vise Jaw: The main tail vise jaw is assembled using the "Condor Tails" joint.

- The Bench Top: Construction begins on the split bench top, with another plan sheet of holdfast holes layout.

- The Front Top Laminate: The front half of the split top is screwed and glued together.

- The Bench Top Cross-members: Are created to connect the two halves of the split top assembly.

- Completing the Bench Base Unit Assembly: The rear half of the top is laminated, attached to the cross-members, and top finish is applied.

- Workholding Fixtures & Vises examines the installation of planing stops, the sliding deadman, and the tail and leg vises.

- The Center Planing Stop Strip: The filler strip for the split top is created, with stepped blocks to raise it for use as a transverse planing stop.

- Bench Top Planing Stops & Dowel Former: Two planing stops are added to the left end of the bench, as well as a dowel former plate.

- Tail Vise Assembly & Installation: The tail vise is finally finished and installed, along with a foot pedal to operate it.

- Leg Vise & Paralell Guide Work: The leg vise and parallel guide are assembled, vise screw adjusted, and the leg vise is finished and installed.

- The Sliding Deadman: This lengthy section addresses deadman assembly, and what I did to make use of my Stanley No. 203 Bench Brackets.

- Wooden Bench Dogs: These were made to occupy the blind dog holes along the front of the bench top and prevent them from filling with debris.

- The Apron Dog Lifter: With all those blind dog holes filled with dogs, I made this contraption to pop the dogs up for easy removal.

- The Double-Screw Vise: Assembly of this bench top unit allows comfortable work on the ends of vertically held stock.

- Bench Hooks & Shooting Boards: A few chunks of scrap turned into a very handy couple of bench hooks, a shooting board, and a sticking board.

- Tool Storage & Shelving covers the addition of the bottom shelf, bench top tool racks, powering the bench, and the tool box.

- The Bottom Shelf: The 5/4 stock that's been kickin' around the shop for months is finally put to use for the bottom shelf.

- Bench Top Tool Racks: Two un-planned tool racks are added to the back edges of each end of the bench.

- Bench Tool Storage Box: Work on the 4-drawer tool storage box for the right side of the bench shelf.

- Power Distribution & Task Lighting: While working on the tool racks, I decided to add some power outlets and additional task lighting.

- Bench Materials & Costs is a detailed list of materials and the entire cost of the project.

- Resources & References has links to a few bench building blogs, and a list of reference books utilized throughout the build.

Bench History & Design

The short-term goal for my bench is to build something I can use to secure my stock for trim and finish carpentry prep work. We now call that work finish carpentry, but 100 years ago this manner of woodwork was referred to as joiners work (as opposed to cabinetmaking - what we call case work now). Eventually I'll have a lot of cabinetmaking / case work to do to furnish the house when the renovation is finished, but I need to get the renovation finished first. While I admire the French style bench, I'm more interested in getting something together fairly quickly and without spending too much money on it. I'd also like the ability to knock it down in to managable parts so I can move it to the garage someday.

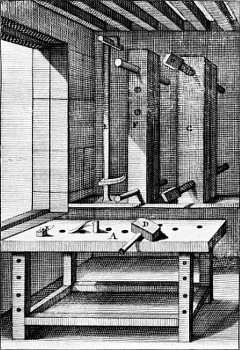

The Joiner's Bench, Fig. 12, Joinery Plate XII

Peter Nicholson's Mechanic's Companion, ca.1831.

To repeat Schwarz's bench design mantra, the bench needs to hold stock so I can work the edge, face, and ends without issues. For what I have in mind, I believe the English style bench is going to do the job nicely. Most of the elements for joiner's bench design seem to have been worked out over the last couple hundred years, so that means a little historical study is helpful to narrow down the design. In addition to Schwarz's wonderful books, Landis's The Workbench Book also offers some interesting design ideas, and most recently Mike Siemsen created the DVD The Naked Woodworker, which features building a Nicholson bench with dimensional lumber over just a couple days.

Drawing upon all these resources I based my design largely on the Nicholson bench (shown at right), with the workholding additions

(leg and tail vise) from Schwarz's first workbench book, then tweaked it a bit using some of the knock-down joints he utilized on his

recent blog posts at Lost Art Press

![]() I like the Nicholson because

it doesn't require the massive laminations (or solid slabs) used for the top and legs on the Roubo, but instead utilizes the large

front apron to tie into the legs and provide dimensional stability. I also got rid of the large rear apron that many others added to

the back (most notably George Ellis, in his 1902 rendering of the English bench, below), since I believe the original open back allows better

access for clamping the far end of stock to the bench. Ellis also improved on the original with his splayed legs to resist planing thrust,

as well as the storage drawer and bottom shelf, which I've also incorporated into my design.

I like the Nicholson because

it doesn't require the massive laminations (or solid slabs) used for the top and legs on the Roubo, but instead utilizes the large

front apron to tie into the legs and provide dimensional stability. I also got rid of the large rear apron that many others added to

the back (most notably George Ellis, in his 1902 rendering of the English bench, below), since I believe the original open back allows better

access for clamping the far end of stock to the bench. Ellis also improved on the original with his splayed legs to resist planing thrust,

as well as the storage drawer and bottom shelf, which I've also incorporated into my design.

The Joiner's Bench, Fig. 1, Chpt. III, Workshop Appliance &c.

George Ellis's Modern Practical Joinery, ca.1902.

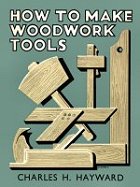

Another design element I found very interesting is from the bench in Charles Hayward's How to Make Woodwork Tools printed in London in 1945. Hayward incorporates the wide front apron of the original Nicholson design to add rigidity, and also like the original, he does not have a matching rear apron. However, the change he made that I really like is that slightly angled rear leg system, (shown below) which like Ellis's splayed legs, helps stabilize the bench during rigourous hand planing operations. Perhaps because of my years of fighting with wobbly sawhorses when trying to hand plane, I decided to add Hayward's angled rear legs to my bench. He also ties the two sets of legs together with a lap jointed spreader at the top of the rear legs, rather then just the two mortise and tenoned spreaders at the bottom. These tweaks from Hayward have been worked into my design, and yes, that means cutting some compound angled pieces, including angled mortise and tenons, to tie it all together.

The "Home Workshop" Bench, Fig. 1

Charles H. Hayward's How to Make Woodwork Tools, ca.1945.

One element that didn't change much over the well documented 150 year history of the English joiner's bench described above, is the method of workholding these gentlemen utilized on their bench designs. Common to all of them, even going back to Félebien in 1676 or Moxon in 1678, is the simple planing stop block that's mortised into the left end of the bench top (Fig.5 & Fig.6 in Roubo's plate XI, above), fitted with a toothed, iron insert to grip the end of a board while planing. Holes in the front apron and legs are shown in both Félebien's and Moxon's plates, although these are likely for holdfasts (Fig.2 & Fig.4 in plate XI), like the holes in the bench top. Félebien didn't show any manner of vise or clamp on the front of his bench, although Moxon did add a crochet or hook (like Roubo's) on the front, which included a wooden screw to clamp boards in place for edge work. This crochet evolved into the face vise on Nicholson's bench, and Ellis shows a small peg at the far right to support the other end of the board, as does Hayward. An early tail vise and row of dog holes shows up in what Roubo calls the German cabinetmaker's bench (more likely Scandinavian) in plate CCLXXIX of his The Art of the Joiner, vol. III of the early 1770s. Schwarz incorporates both the leg vise on the front left, at a 20° angle, and a wagon / tail vise with a row of dog holes in the top. My bench will make use of the leg vise and tail vise, and of course holdfasts and a planing stop in addition to a row of dog holes for work holding.

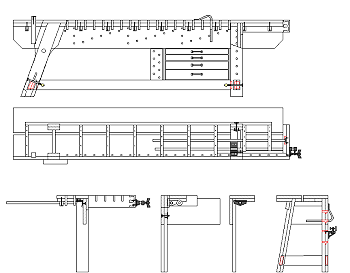

With a pretty good idea of what I wanted as an end result, I set about making a set of plans to get things started. My workspace will accomodate a 10 foot long bench without too much trouble, and that length will allow me easily secure standard 8 foot long lumber for making trim pieces. The overall bench design is a combination of Schwarz's English bench from his first book, along with a sprinkling of changes from other historical sources outlined above. Both back legs will get sloped toward the front at a 10° angle (from Hayward), and both left legs will get a 20° slope toward the center (Ellis/Schwarz). The right front leg will not be sloped, but I plan to add an angled semi-dovetail to the top where it joins the apron, as Nicholson shows. The leg pairs will be through tenoned top and bottom with a wide board at the top, and a double-thick spreader at the bottom, then these assemblies will get joined at the bottom with a pair of long spreaders front and back, which may be dis-assembled using a set of Veritas bench bolts. A third full-length spreader will be lap jointed and through bolted to the top of the rear legs as well, which will allow the top cross supports to hook underneath the spreader and help hold the top in place. The bench height will be 34 inches, and the depth 23 inches, with a slot running the length of the top with a removable board that may be shifted to raise above the top for use as a planing stop.

For workholding I'm planning to install the traditional planing stop block in the left front corner, as well as employ a variety of 3/4 inch holes in the top for Gramercy holdfasts. The front apron is also peppered with holes for holdfasts, and the left leg and sliding deadman will have a slightly different hole size in them to make use of a pair of Stanley No. 203 bench brackets. An angled leg vise will get fitted to the left front leg, and I'm going to try out a relatively new tail vise arrangment by using the Veritas pipe vise. The tail vise will appear as a traditional Scandinavian "L" shaped tail vise aligned with a set of dog holes along the front edge of the bench top, however the pipe vise unit should allow me to extend the tail piece far enough to secure 10 or 12 foot long stock, assuming I can overcome any sagging problems when I attempt to extend it that far out to the right. The 2-3/4 inch thick top will have no apron along the back to allow the use of clamps with the top, and I intend to install a small tool storage unit at the far right, along with a full length shelf supported by the spreaders. The tool storage shouldn't interfere with holdfasts coming through the top, since the front apron limits the height of the storage box. Now I just need to build it!

Building the Joiner's Bench

Stock Preparation: Fall 2014

Once I'd decided on the basic design and dimensions, the first step to actually making the thing was to get the stock to make it. I decided

to use Southern Yellow Pine for the top, legs, and spreaders, with standard Spruce dimensional lumber for blocking and laminations to add thickness

to the top and front apron. Obtaining Southern Yellow Pine in New England can get expensive, however all the pressure-treated stuff here is made

with Southern Yellow Pine... So yes, I'm making my bench from pressure-treated lumber.

I purchased all of the pressure-treated stock I thought I'd require in August, which was one 2x4x10, five 2x6x10, one 2x10x12, and three 2x12x12, then stacked it all on edge in the shop and let it sit for a few months to dry out while I worked on other projects and bench plans. I don't have a moisture meter, but I could tell by the weight of the boards that it was getting to be time to start working on them by late-November. Ideally I'd hand plane all this stock to provide clean faces and edges, but without a proper bench and faced with the amount of lumber I had, I instead contacted a cabinetmaker friend of mine with some massive power tools and ran all the stock through his thickness planer and jointed an edge. He also picked up a massive 3 foot long chunk of 10/4 Poplar that I'll use for the leg vise chop and planing stop, and we ran that through the planer while we were at it.

The finished thickness of all the stock ended up being 1-3/8 inch, and with that dimension set I could then return to the plans and start working on the details of the leg assemblies (without knowing the finished dimensions, trying to get all the measurements figured out just doesn't work). I also purchased the five 2x10x10 pieces of Spruce that I'll need for the underside of the top and apron. With the Spruce stacked to dry and all the pressure-treated ready, I began working on the details of the leg assemblies.

Leg Cutting & Glue-up: early Winter 2014

With the 2x6 stock jointed on one edge and faced, I finalized the leg layout so I could start cutting stock and getting the leg

pieces glued together. Each leg is made from 2 pieces of 2x6 glued and screwed together, and I took some care to ensure I cut the

pieces from the same board when pairing up the chunks for assembly. That way if there was any cup on the board, the pieces would still

fit nicely, and all the grain would match up for finish planing. Each leg was glued and screwed together in the shop, then brought inside

to sit in the clamps overnight while the glue dried. I used Titebond® III Ultimate waterproof PVA glue, since

the thing is going to be kept in an outdoor plastic shed, and I like the longer open time of the III over their other PVAs.

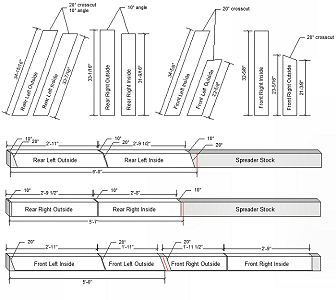

The layout and final dimension for the legs was fairly tricky, since each leg (other than the right front), has a couple angle cuts to deal with, and the stock dimensions were still not quite final. After an edge was jointed the stock was 5-9/16" wide or so, and after glue-up I ended up planing down the unfinished edge (along with a couple light passes on the original jointed edges) to give a finish width of 5-3/8". Everything had come back from the thickness planer at 1-7/16" thick, and the plan was to hand finish it down to 1-3/8" (2-3/4" actually, since almost every piece for the bench is made from double-thick stock that's glued and screwed together). One of each pair of leg pieces is longer than the other as well, so it will fit into a mortise in the top, or to create an oversize lap joint with the front apron.

Rather than try and measure everything then make perfect cuts, I just started with the rough cuts shown on the bottom part of the leg plan sheet then rigged together a layout jig so I could measure and mark the compound angle cuts accurately. The jig consisted of a 3-foot square chunk of plywood on the floor of the shop that was leveled with shims. I then clamped together a pair of angle cut leg pieces, and stood them on the plywood with the top end leaning against a sawhorse. I then put a piece of scrap 1-7/16" thick cut-off on the top leg angle cut, tweaked the leg to ensure the top was level, and clamped the whole thing in place against the sawhorse. The last step was to stand up a 3-foot steel rule, ensure it was plumb with a 2-foot level, mark the finished height of 34" on the temporary top piece, then mark off the offsets for the long leg height, and step off again for the short leg height. Like I said - fairly tricky, but I know the cuts are correct now. The measurements that ended up on the top part of the plans were taken from the finished legs (which is why they're a little odd), rather than attempting to work out the compound angle cut measurements first then cut to those lines. Scribing from marks on the actual stock always ends up being more accurate than trying to cut to measurements, it seems.

More Stock Prep - Mortise & Tenon Work: late Winter / early Spring 2015

I had managed to get all the leg pieces glued together before I crushed my finger at the end of 2014, but then the project was put on hold

for the rest of the Winter until I could get my hand working again after many weeks of physical therapy. It wasn't until March of 2015 that

I was given the go ahead to return to work, so that's where we pick up the bench project once more.

I had my Vanagon back from the shop at last as well, so the next step was to get the Spruce stock over to my friend's cabinet shop for thickness planing and edge jointing, then I got all that stock glued up to make the wide material that I'd use for adding thickness to the top pieces and aprons. With all the stock ready to go, I then glued together the double-thick bottom side stretchers, and cut the top side stretchers to length.

Next I started having fun with mortise and tenon joinery. As much as I would have enjoyed cutting all these joints by hand, since I didn't have a proper bench to hold my material while working it, I just went the power tool route and used the router to make the tenons. First I laid out the tenons by marking a line around the end of each stretcher (with about an extra 1/2 inch of length or so), then chiseled a little trough all the way around to ensure I could see the shoulder. I then used a Freud® 1-1/4 inch diameter flat-bottom "mortising" router bit, set for a 5/16 inch depth of cut, to waste away most of the material and define the sides of the tenon. The top and bottom shoulders of the top stretchers were then cut in with the band saw, while the bottom stretchers got the 5/16 inch cut on all four sides. All the tenons were then cleaned up by hand with chisels and a medium shoulder plane.

With all the leg stretcher tenons done, I then turned my attention to cutting their mortises in each leg. As I'd done for the tenons, I again used a combination of power and hand tools to get the job done. I started with the top stretcher mortises, and cut those using the plunge router with the edge guide fence attached, and a 3/4-inch upcut spiral router bit (remember, the stretcher stock is 1-3/8 inch thick, and the 5/16-inch deep cuts on each face for the shoulder results in a 3/4-inch thick tenon). Because the top stretchers are set parallel to the legs, using the guide fence with the router ensures everything lines up correctly. After routing, a little clean-up by hand with a chisel for the corners and to get the top and bottom angles right, and the top stretcher mortises were good to go.

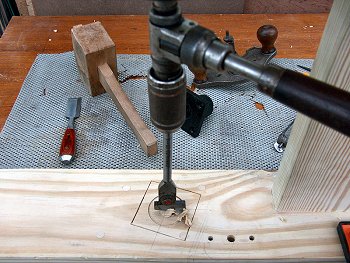

The bottom stretcher mortises were a little more challenging to get right, since those are not cut parallel to the legs. Rather than use the router, I went for a 1-inch self-feed bit in the power drill to get through the stock, then cut the rest out with the jig saw. I started with some careful measuring and marked the outline of the mortise with a chisel all the way around, then ran the drill bit in at each corner about half-way through the leg. I then flipped the leg over, and did the same thing from the other side. The leg mortises required a lot more hand clean-up work (a drill press with a Forstner bit would have made the initial holes much cleaner, but I don't have a drill press in the shop...), but the good news is these mortises are big enough that I could get inside them with the shoulder plane and everything cleaned up nicely with that.

Leg Unit Assembly - Drawboring

Assembling the leg unit mortise and tenons was done using a technique called drawboring. Drawboring requires a little extra time to get right,

however the result is a very strong joint, and clamps are not needed for final assembly (which is nice for me since I have a few angled

surfaces to deal with). To create a drawbored joint, the mortise and tenon are assembled with a pin driven through the joint, however the hole

for the pin is offset on the tenon from the hole through the mortise. When the pin is driven through the assembled joint, it draws the

tenon shoulder tight up to the piece with the mortise, creating a strong mechanical joint that doesn't require glue.

To begin assembly, I drilled a 3/8-inch hole through all the leg mortises for the pins. Each bottom stretcher mortise got one hole, and each top stretcher got two holes. I placed the hole about 3/4-inch back from the shoulder side of the joint, and bored it all the way through the leg. These holes are drilled without the stretcher tenons in place, although I did wedge a chunk of scrap into each mortise to prevent any tearout on the inner mortise walls while drilling. Next, the stretcher tenon is dry fit into the mortise, then the drill is inserted into the hole to mark the hole location on the tenon. The stretcher is then removed, and the tenon hole is drilled with a small offset toward the tenon shoulder. That's the part that gets a little fussy and requires some extra time.

I found that getting the point of the bit to move after marking the hole was a little dicey (the bit wanted to slide back into the marked spot, rather than bite into a new spot 1/16-inch closer to the shoulder), so I came up with a method that gave me a little more wiggle room to make the new hole in the tenon. When marking the hole location, I put the stretcher into the mortise, then added a couple thin shims to the shoulder and clamped the stretcher into position. I then put the auger bit into the mortise hole and gave it a little twist to mark the tenon from both sides of the leg. After removing the stretcher, I could then measure over a full 1/8 inch from the mark (the thickness of the shims, plus another 1/16-inch or so), and the drill bit would stay clear of the original mark. I drilled into the tenon from both sides to ensure the hole was correctly aligned, and the parts were ready for assembly.

The pins were cut from 3/8-inch Poplar dowel stock, and I sharpened the ends with a Stanley No. 22 dowel sharpener. Even though a drawbored joint doesn't require glue, I still added a little to the inner mortise walls, then slid in the tenons. I then pushed a 3/8-inch drawbore pin into the hole and wiggled it around a bit to help get things lined up, and finally drove the pins through to pull the leg assemblies together. I let them sit overnight for the glue to dry, then spent another day with the flush cut saw and belt sander getting everything cleaned up. Now it's time to add the stretchers to tie these leg assemblies together.

Stretchers & Bench Bolts: Spring 2015

The two bottom stretchers were ripped from a single 2 x 10 on my friend's table saw, then one edge jointed and each was planed to

4-1/4 inch by 1-3/8 thick. These bottom stretchers would get a shallow tenon into each leg, then get attached with

Veritas® Special Bench Bolts

![]() (1/2"-13 x 6") to allow for dis-assembly

if I ever need to move or store the bench.

(1/2"-13 x 6") to allow for dis-assembly

if I ever need to move or store the bench.

Once the stretchers were dimensioned, I then cut the tenons on the ends for the right leg first, since those fit into the leg at a right angle and would be a little simpler to lay out than the angled things on the left end. I want the front stretcher to be flush with the front of the legs (and front apron), but didn't have a lot of room to play since the outside of the leg would need a 1-1/4 inch countersunk hole for the washer under the through bolt. I decided to make the tenons 3-inches tall (5/8-inch shoulders top & bottom), then offset the shoulder from the outside a tad to give more room for that countersunk washer hole while still keeping the through bolt hole within the tenon by trimming off 5/16-inch for the outer shoulder and 3/16-inch for the inner, leaving myself a 7/8-inch wide tenon. The tenons were marked out and cut using the router, just as I'd done with the short leg stretchers, then the mortises were marked and cut into the legs using an auger bit for waste removal, and chisels for clean-up. I then took a couple shaves off each check of the tenon with the shoulder plane to ensure an easy fit into the leg mortises, and set about getting the bench bolts installed.

Bench Bolts Installation

Installing bench bolts sounds a lot easier than it is when dealing with 8-foot long stretchers, but the first thing to do is get the holes

for the bolts and washers into the outsides of the legs - that part isn't bad. Since I don't have a drill press available, I needed to come

up with a way to ensure the holes were straight through the legs. I came up with a "portable drill press" of sorts by using an upcut

spiral router bit in the router with the plunge base. That allowed me to get the hole started with a couple inches of depth that was straight,

then finish it with an auger bit in the hole started with the router.

First the hole location is carefully marked on the outside of the leg, then the router plunge base and fence is placed onto the leg. The router is fitted with the 1/2-inch upcut bit and put into the base with the tip of the bit just off the wood surface, then the whole works is tweaked to ensure the hole is aligned correctly and the router base is clamped into position. The router is then removed from the base and 1/2-inch bit is replaced with the 1-1/4 bit, which will be used to make the countersink for the washer. With plunge base the depth stop adjusted appropriately, the big bit is plunged into the leg to create the countersink. The router body is then removed from the base again and the bit swapped back to the 1/2-inch spiral upcut (but the base remains clamped in position). The router then goes back in the base, and the upcut bit is plunged into the leg as far as it will go to create the beginning of the through hole for the bolt. All the router stuff is then removed and things get interesting...

In order to get the hole through the leg and into the stretcher in the right position, the stretcher needs to be installed in the leg and held

there, which is no small matter with an 8-foot long stretcher. I've seen some

right-angle carcass clamps![]() that may work

for this sort of thing, but I don't have any and didn't want to wait a week to get them, so I needed to come up with another way to clamp

those stretchers into position. After lots of fiddling around with blocking and F-clamps to hold the leg assembly to the bench, I clamped the

stretcher into position with a couple pipe clamps that were hooked to each other to get enough length and grab the end of the stretcher. I then

used the ratcheting bit brace to extend the bolt hole through the leg and into the stretcher as far as it would go. The stretcher was then removed

from the leg assembly, and I used the bit brace to bore into the stretcher until it bottomed out. I then fitted a 3/8-inch bit into the brace and used

it to try and clear all the chips out of the hole, then the stretcher was clamped back into the leg assembly to mark the location of the big brass nut.

that may work

for this sort of thing, but I don't have any and didn't want to wait a week to get them, so I needed to come up with another way to clamp

those stretchers into position. After lots of fiddling around with blocking and F-clamps to hold the leg assembly to the bench, I clamped the

stretcher into position with a couple pipe clamps that were hooked to each other to get enough length and grab the end of the stretcher. I then

used the ratcheting bit brace to extend the bolt hole through the leg and into the stretcher as far as it would go. The stretcher was then removed

from the leg assembly, and I used the bit brace to bore into the stretcher until it bottomed out. I then fitted a 3/8-inch bit into the brace and used

it to try and clear all the chips out of the hole, then the stretcher was clamped back into the leg assembly to mark the location of the big brass nut.

The 6-inch long through bolts that came with the Bench Bolt Kit weren't going to be long enough for my needs, so I replaced those with 8-inch stainless steel bolts from McMaster-Carr. I now needed to mark the location for their matching nut on the stretcher. Even with all the care given to try and get the through holes for the bottom stretchers nice and straight, they still end up being a little off so I find it's best to mark the location of the nut, rather than try to measure the location on the stretcher. To accomplish this, I made a little jig using a block of scrap wood with a couple lengths of 1/2-inch dowel sticking out of it (see photos). The dowel that goes into the leg hole is about 6-inches long, and the other dowel is about 10-inches long. The holes in the block for the dowel are carefully marked off the edge to ensure they're lined up, and they're then made with the upcut spiral bit and the router as before, to ensure they're straight. A bolt is then placed next to the long dowel, and allowing a little room for the countersunk hole, the center of the threaded portion is marked on the dowel. A little hole is drilled through the dowel at that mark, and a brad is inserted that will be used to mark the spreader nut location. With the spreader clamped in place again, the jig is then inserted into the leg hole, squared to the leg, and the brad is gently pushed onto the stretcher to mark the nut location. Everything is then dis-assembled, the hole is bored for the nut, and things are then re-assembled.

The stretcher mortise & tenons and bench bolt location for the left legs went along pretty much the same, with a couple minor alterations. To get the stretcher length correct, the location where the top of the stretcher contacts the leg is marked after carefully measuring from the right side top shoulder, then the left leg assembly is clamped into position against the stretcher and the angle for the left stretcher shoulder is marked into the stretcher. The tenon shoulders for the left end are also cut at an angle (the end of the stretcher is straight), so the top the tenon is a couple inches long, while the bottom only protrudes from the stretcher about 1/4-inch. This allows the stretchers to be attached to the right leg unit first during assembly, then brought up into the angle mortise of the left leg unit and bolted into position.

Top Stretcher Installation

The top rear stretcher is cut from a 2x4x8, then connected to the leg units with a modified half-lap dovetail joint and through bolted into

position. This top stretcher serves an important role in that it holds the two leg assemblies in place while assembling the bottom stretchers,

and also acts as a retainer for the bench top. Because it is installed against the back legs, it meets the top at a 10° angle and provides

a place underneath which the angled ends of the bench top cross-members will be held. The joints for the top stretcher were cut using the mortising

bit in the router as usual, then cleaned up with hand tools (see photos for details). The top stretcher is held in place using a single 3/8-inch

stainless steel bolt & washer at each leg unit, through bolted into a

threaded rod mounting plate![]() from

McMaster-Carr, mounted on the inside of the leg unit.

from

McMaster-Carr, mounted on the inside of the leg unit.

With the stretchers finished, the next step is to make any remaining holes for workholding fixtures in the leg units, get the shelf rails mounted to the two bottom stretchers, then apply the finish to all the base pieces so it can be assembled.

Mounting Assembly & Workholding Hardware in the Bench Base

Before applying stain and finish to the bench base assembly, I wanted to get all the holes made so I'd only need to stain everything once.

That meant I needed to get the hole locations for the leg and tail vise hardware figured out, cut the mortise for the leg vise parallel guide,

make the holes for the front apron mounting plates, and add additional dog holes to the right leg unit. I also needed to get the shelf supports

installed on the lower stretchers, and add a track for the sliding deadman to the front stretcher as well.

I began with the apron mounting plates, using the method I'd come up with of using the plunge router with an upcut spiral bit as a "portable drill press" to ensure all the holes I made were straight. After getting two mounting plates installed for the apron on each leg unit, I turned my attention to the vise hardware. I opened the box for the leg vise screw to examine the threaded base, and realized that the thing is supposed to be mortised into the leg, and not just screwed on to the inner surface. I should have checked the base before assembling the leg unit, since it would have been a lot easier to get the hole made before the leg unit was assembled. It ended up going pretty well, since I still had enough room to get in there with the Stanley No. 984 short corner brace, fitted with an Irwin No. 22 expandable bit. I then had to make a decision about the parallel guide location and whether to put that above or below the side leg stretcher. I like the idea of keeping it low, so I made the 3/4-inch wide mortise for that just below the mortise for the leg stretcher. In order to have enough room for the thing, I made the mortise flush with the stretcher mortise on the outside of the leg, then plowed a groove in the bottom of the stretcher on the inside of the leg stretcher for the guide to ride in. I then moved to the right leg unit and the tail vise base, which was simply clamped into position, then holes for mounting bolts were drilled using the vise base as a guide.

Readying the Base Parts for Finish

With all the holes for base assembly and hardware done, I still needed to make the shelf rails and sliding deadman guide for the lower stretchers.

I cut a pair of rails to 1-1/2 inch square, then planed them down to 1-3/8 inch square to match the rest of the stock thickness. Each rail was clamped to

the stretcher, then I used a piece of 5/4 preassure-treated decking to determine the offset from the top of the stretcher for the shelf. I want a

little gap between the top of the stretcher and the tops of the shelves, so I added about 5/16-inch and marked the distance. The result puts the shelf

rail almost centered on the stretcher, which meant I also needed to bore some holes at each end of the shelf rails for clearance to insert the bench

bolt nut during assembly.

The last piece needed for the base was a guide for the sliding deadman on top of the front stretcher. Because the deadman only runs part way across the front of the bench (there's 2-foot, 6-inches on the right that will be occupied by the tool storage box), I decided it would look better to add the guide to the stretcher, rather than mill away the stretcher and make it look oddly narrower on the right under the box. I ripped a piece of stock about an inch square, then took off the two top corners at 45° with the band saw to rough out the guide. I then planed smoothed one of the 45° faces, and attached the guide to the stretcher, offset a 1/4-inch from the face, with plugged screws and glue. The offset was added so the sliding deadman base will have a small square edge at the front, rather than a fragile point. After the glue dried overnight, I then belt sanded and planed the angle on the back of the guide until it was flush with the back face of the stretcher.

The last step prior to finish application was to go over all the base parts and ease the corners of everything with the 45° guided chamfer bit in the router. I didn't want the chamfer to just disappear where parts met, so I marked an offset of one inch wherever two pieces joined each other. This offset would leave a flush or square transition, and I think it adds a nice detail. I also had a piece of stock left over from the shelf rails, so I decided to add an extra crossbar inside the left leg assembly that is installed so it is at the same height as the top of the tool storage box (flush with the bottom of the front apron). This will provide a place to hang F-clamps, or store long stock beneath the bench top. The crossbar and shelf rails were given their edge chamfer prior to assembly, then I went over all the edges of the stretchers and leg units with the router. I also took the extra few minutes to finish the end of each chamfer with a bullnose shoulder plane and chisel to give a crisp, stopped chamfer, rather than the rounded end left by the router bit. I then screwed and glued the shelf rails and crossbar into position, gave everything a final wipe down with mineral spirits to remove layout lines, then hand sanded all surfaces with 150 grit paper to ready the parts before ragging on a coat of Minwax® Wood Finish™, English Chestnut 233, oil-based wood stain. After two coats of stain, everything then received a couple coats of Minwax® Tung Oil Finish to add a little lustre.

Working the Front Apron: late Spring 2015

After a few days of finish application in the shop, I brought all the parts inside so I could assemble the base on a level floor and start

work on the front apron. The first thing to do was get the half-dovetail lap joint cut into the apron for the right leg, then I clamped the

apron into position against the base assembly. With all the bolts for the base assembly loose, I then did a lot of careful measuring and tweaking

to get the right leg (which determines how the tail vise will align with the top and apron) aligned and square with the apron. With everything lined up

nicely and clamped, I marked the holes for the front apron bolt holes by inserting a brad point bit though the hole in the leg (with the mounting

plates removed). I then took the apron back to the shop, bored the bolt holes using the 3/8" upcut router bit, then installed the mounting plates on the

legs and bolted the apron in place to check the fit. The apron had been cut a little oversize in width and length, so now that it was bolted in place

I could make the final marks for length and return it to the shop for final dimensioning. I cut it to length, then hand planed it smooth to remove about

1/16" of material and knocked off a couple 45° cuts on the outside bottom corners. I then bolted it back into place and jointed the top edge

even with the tops of the legs.

With the front apron cut to finished size and fitted in place, I then spent some time with the plans open on the computer and marked all the locations for the twenty five front dog holes. Because I'll glue and screw a second board to the back of the apron to increase thickness, I want to have all the dog holes laid out first to ensure I don't end up with any assembly screws in a dog hole location. I also marked the location for some additional through bolts that will connect the apron and top together, as well as a couple bolts that will hold the tail vise frame in place. Once I had double checked all the hole locations, I then removed the apron and took it back to the shop for lots of hole making.

The first step to "perforating" the front apron was to use a 3/4-inch auger bit in the hand brace and give a couple turns at each hole location to mark the hole diameter in the apron. Then it was back to the "portable drill press" plunge router set-up with the 3/4-inch upcut spiral bit and fence to bore all the holes through the apron. After lots of clamping and tweaking all the holes were done. I then made the 1/2-inch deep counterbores for the assembly bolt heads and washers with a 7/8-inch auger bit, and finished the through holes for the bolts with a 9/16-inch bit. Next, I flipped the apron and routed out a 2-1/4 wide, 7/16-inch deep dado for the planing stop block that fits into the apron just past the leg vise on the left end. Because I want the planing stop to align with the dog holes and tail vise in the top, it's located fairly close to the front of the bench, and the apron needed to have a little material removed to ensure everything lines up correctly. I also routed a 1/2-inch wide, 3/4-inch deep rabbet along the lower inside edge of the apron that will form one half of the 1-inch wide groove to house the top of the sliding deadman (the other half will be a rabbit in the back board for the front apron). I also noticed a split in the far left end that worried me a little, so I added a butterfly/dovetail key to help control that. The last thing to do before adding the backer board is to carve in my name and date on the right end of the apron below the tail vise location, but that will have to wait a couple weeks for my hand to recover from the second surgery to repair my flexor tendon.

The Front Apron Backer Board

With the incision from my second surgery healing nicely, I was able to get back to the woodshop near the end of May and take care of more work on

the front apron. Before gluing the backer board in place, I did some incised letter carving on the right end of the apron and added my name and date

to the bench. This was my first attempt to letter carve, so I spent less than twenty bucks on a set of tools from China (on E-Bay) to just try it out.

I also picked up a nice fishtail chisel from Lie-Nielsen for getting into the seriffs (and to use for dovetail work later on). I laid out the lettering

on the computer then printed a full-size image of what I wanted. I then spray mounted that sheet to the apron, and cut the outline and center-line for

all the letters into the bench. Once everything was marked out I removed the template, and carved out the rest of the letters. For a first attempt, I'm

quite pleased with the results.

Next I turned my attention to the front apron backer board. This piece would add mass to the bench, provide the thickness to the apron for holdfast and planing stop use, and create the other half of the track for the top of the sliding deadman. I cut the 1/2-inch by 3/4-inch rabbet for the deadman first, then added a notch to the right end of the groove to create a location to remove the deadman from the bench. It seems the "normal" way to make the deadman removable is to make the groove deeper than the tenon on the top of the deadman and leave an extra inch or so of clearance between the upper groove and shoulder on the deadman, then lift the deadman into the groove and swing the bottom off the lower track. I didn't like the idea of having all that extra space above the deadman, so I decided to make a spot at the top right end where there was room to swing the top back out of the track, yet keep the deadman captive for the rest of the track length without all that slop at the top. I made a little gizmo (see photos) for the back of the backer board that I could pivot out of the way to remove the deadman, but in use it would keep the deadman in place so the thing never accidently falls out of the track.

To get all the backer pieces attached in the correct location, I then clamped a long strip of scrap to the apron (along with another piece of scrap to the front so I didn't leave clamp marks on the apron) that was the same thickness as the top backer board - the way this thing fits together is the top backer board sits on top of the apron backer board, and the top sits on top of the apron, so I needed this spacer to get the stair-step arrangement of everything properly aligned. I then added the backer piece for the left end of the apron that fits fromt the end to the plaing stop slot, and another backer piece between the planing stop and the left leg. Those two pieces were glued and screwed in place, then I set about marking the long apron backer with all the locations of the top dog holes and front through holes so I wouldn't put any screws into a hole location during assembly. With everything carefully measured and marked, I gave the apron and backer a healthy coat of glue, clamped them together, and screwed the whole works together with a screw every few inches. After the glue cured overnight, I then scraped and belt sanded the back, planed all the edges, and sanded the front to ready the apron for finish application.

The Tail Vise Frame: early Summer 2015

After a few coats of finish to the front apron piece, all parts were brought inside so I could assembly the bench once more on a level floor

and start working on the tail vise. Over the course of building the base frame and front apron, I'd given a lot of thought to how exactly this pipe

vise unit I'd decided to use was going to function (or not). My original idea was to use the pipe vise so the tail vise would work both as a

"standard" tail vise with at least 12-inches of travel, but then also allow the option to extend it out a few feet to hold 10 or

12-foot stock when needed. The plan was to use a pair of 3/4-inch pipes (one for the clamp mechanism and one to act as a guide bar) that would

rest against the bottom of the bench top so when extending the tail vise jaw, the pipes will prevent it from sagging and flopping around. As I worked

through the details of how this was actually going to function, it became clear that I would need a lot of blocking under the right end of the bench

to support all this stuff. I ended up building a fairly massive vise frame unit that gets attached to the bench assembly after the apron and legs

are assembled.

Before applying finish to the front apron, I had cut a notch out of the right end above my name to accommodate the tail vise jaw unit. I then set about making the front part of the jaw unit using a piece of offcut from the original front apron stock so the grain would match nicely yet the piece would have the extra length to attach the end of the jaw unit. This piece was then glued and screwed to additional stock to create a roughly 4 by 4-inch front jaw that will have a few dog holes in it, and a sliding dovetail to act as a guide. This front part of the jaw would also sit on the vise frame shelf that gets attached to the apron and upper leg assembly cross-member with a few 3/8-inch knock-down fasteners. The sliding dovetail of the jaw piece then fits into a matching dovetail that is attached to the shelf frame. The shelf frame dovetail piece also acts as a guide for the main vise clamp pipe, which meant it needed a 1-inch diameter hole through the length of the piece. Rather than attempt to drill an 18-inch long hole, I made the guide piece from two pieces of stock with cove cut in them with a 1/2-inch deep by 1-inch diameter router bit. I then cut the sliding dovetail in one of the pieces, then glued and screwed the two pieces together to create the guide block.

With the shelf and front jaw guide fitted, I started work on the rest of the frame that would house the guide bar for the vise jaw. My original idea was to built a sort of box from dimensional lumber with a flat face at the end, and couple cross-members spanning the frame shelf to support the top and the guide bar. The more I delayed in making the thing, the more I became convinced that wasn't really going to work. Instead, I ended up laminating a solid block that fills the entire area between the front half of the bench top and the tail vise shelf. I laminated together another couple pieces of stock with a 1/2-inch by 1-inch cove to form the long guide bar hole, and also ripped a couple of the pieces so they would form a hole in the top of the vise frame that would accept a block that's attached to the bottom of the bench top to help align everything. Please see the photos to help make sense of what I'm attempting to describe.

The Tail Vise Jaws

While getting finish applied to the tail vice frame unit, I moved on to creating the tail vise jaws. The front jaw stock with the sliding

dovetail was ready for more work since I'd needed that to get the frame aligned, but I still needed to get the end jaw built. This piece was

going to be rather tricky as it needed to house the base for the guide bar, and also hold a couple captive nuts to secure the tail vise pipe clamp

head. I wanted to use a nice dovetail joint to join the two jaw pieces together, but I didn't want to try to work on that joint while the end

jaw had a five-foot long pipe sticking out of it. I decided to first temporarily screw together two of the three pieces of end jaw stock and use

that chunk to get the guide bar base fitted, then I could attach the base to the third piece of stock and screw that piece on to have a finished

jaw piece on which to layout and cut the dovetail. Once the dovetail was ready for assembly, I could then remove the screws and attach the guide bar,

then glue and screw the end jaw back together while assembling the dovetail joint with the front jaw.

Rather than go into all the detail here of creating the dovetail joint for the end jaw, I recommend the article

How to Make 'Condor Tails'

![]() by Jameel Abraham of Benchcrafted. The article

provides excellent step by step instructions and photos for creating the joint, and is also available as a PDF through the link provided.

by Jameel Abraham of Benchcrafted. The article

provides excellent step by step instructions and photos for creating the joint, and is also available as a PDF through the link provided.

With the end jaw pieces cut a little oversize and the dovetail complete, I then glued each piece to the front jaw over the course of a couple days. The first piece went in without any difficulty, then the inside of the second piece needed to have a section cut out to house the threaded base of the vise guide bar before it could be glued into position. After a lot of test fitting to ensure the guide bar didn't bind within the frame and with the pipe securely screwed into the base, I marked the location of the guide bar base on the jaw, and took everything back to the shop to assemble the second piece with the guide bar in place. After the glue cured overnight, I then added the outer end jaw piece with glue and screws through the whole works, and again let the glue cure overnight. After a bit of clean up with the block plane and belt sander, the tail vise jaw was mostly complete - the top piece of the jaw will have to wait until the bench top is done so it can be planed flush to the top.

The Bench Top: mid-Summer 2015

I planned to make the bench top from a double thickness of stock to provide mass and adequate thickness for holdfasts, just as I'd done with the

front apron. I had also taken some care to attempt to make the top so it will stay in place without and fasteners visible on the bench top - there

were some fasteners along the front that connect the top to the apron, but nothing planned between the top and the legs. The idea was that the top

would be a loose fit into the base assembly with cut outs in the backer board to fit around the tops of the legs. The apron bolts will prevent it from

moving around and keep the front edge in line, but as the top expands and contracts it will be free to move as needed along the width of the boards.

The top and backer boards are glued and screwed together just as the front apron boards are, but the cross-members that hold the two top boards together

would only be fastened with screws to allow for seasonal movement. It all seemed like a good idea - we'll see how it works out...

The first step for assembly was to cut the backer board for the front board to size so it would fit between the leg cross-members. This didn't have to be a perfect fit, since I wanted to allow for movement and ensure I could lift place the finished top in position without binding. I laid the backer board in position then simply traced the outline for the tops of the legs onto it and made the cuts. I also marked the position of the two front connection knock-down fasteners, then drilled the holes in the top for the round brass retainer nuts. These holes did not go all the way through the backer board - I only made them deep enough for the threads to catch, then with the backer board clamped into position I put a liberal squirt of silicone into the nut hole and snugged up the bolts. The silicone will hold the nuts in place during assembly, but also allow a little bit of movement for expansion and adjustment if needed.

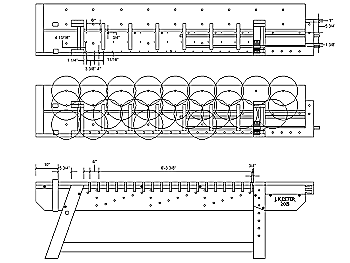

With the center backer board cut to length (and left a little wide at the back), I then went back to the drawing board and spent some time working out the exact location for all the bench dog and holdfast holes, as well as the cross-members. Before I glue and screw the top laminates together, I want to be sure I don't end up with a screw interfering with a hole position later on. The front dog holes are spaced 4-inches apart, so for the front edge I just centered a screw between each dog hole. For the rest of the bench top, I laid out the holdfast holes based on the diameter of the coverage of the holdfast arm (which is about 13-inches). With a little tweaking a worked out that I could put another screw every 6-inches down the center of the top board, and then at the same spacing along the back edge of the board. See the plan sheet above for details.

Assembling the Front Top Laminate

I wanted to make the lamination with everything in position, rather than glue the boards together in the shop then have to trim them to fit between

the legs afterward. I pre-drilled and countersunk all the fastener location in the backer board, then placed the backer board in position within

the base assembly and laid the top board in position to do a final test fit. I noticed the top and backer board both had a little twist to them,

so I "cheated" a little and made a series of shallow cuts with the circular saw in each board, perpendicular to the twist and avoiding

any hole locations, to relive the tension and allow the boards to easily clamp flat during assembly.

To ensure the whole thing would fit easily, I placed a bunch of 1/16-inch thick cardstock shims along the top edge and both ends of the backer board before bolting it into position. The shims made the backer board stick up just a little above the edge of the apron so there would be good contact when clamping, and also made certain the backer board was centered between the legs. I then lined all the edges of the leg assembly with plastic wrap so any glue squeeze out during clamping wouldn't stick to the leg assemblies. The front edge of the top board was positioned so there was a slight overhang at the front apron (which will be planed flush later), and the back edge (which had been jointed square long ago at my friend's shop) was just shy of the edge of the backer board (so the backer board can be planed even with the top after assembly). Both ends were a little long, so those will be trimmed to fit after the glue's set. Satisfied with the fit and position, I then flipped the top board and gave all contact surfaces a generous coat of Titebond® II Extend Wood Glue with a small roller, then put the top back in position and clamped everything together. As soon as the clamps were in place, I then put in all the screws I had access to (the front edge was blocked by the apron), and let the whole thing cure overnight.

Next I brought the top assembly back to the shop and cleaned up all the edges and removed any glue squeeze out, then put in any screws I didn't have access to during clamping and installed plugs in all the screw holes. While the plug glue was drying, I set to work on the backer board that fits at the end with the planing stop. The stock was cut a bit undersize, then the top was placed back on the bench and the backer board clamped in position to get marked for the planing stop cut out. After marking the backer board, the planing stop opening was cut out with a jig saw and cleaned up with rasps and sandpaper for a good fit. Back to the bench with the backer board, and the top was now marked for the planing stop. The top was then taken back to the shop, and I created a planing stop cut out pattern with a piece of scrap 1/4-inch plywood. After ensuring the planing stop block fit easily through the ply, I then screwed the plywood to the bench (the holes won't be seen when the top is laminated), aligning it with the marks from earlier, then used a top bearing flush cut router bit (the one I'd used to cut the "condor tails") to cut the opening for the stop block. After a little clean up with a corner chisel the top and backer board end piece were glued together at the bench.

Installing Top Cross-Members

The last work on the front part of the bench top was to make and install the seven cross-members that hold the two section of the split top

assembly together. These were milled to 1-3/8 inch by 2-inch by about 15-inches long. I then removed all the shims and plastic from the bench top

and bolted the top into position. I laid out and marked where each cross-member went on the bottom of the bench top, then measured the distance to the

rear top stretcher to get the proper length for the angled end of each cross-member (less a 1/16-inch on each end so ensure I can sit the top into

position when assembling the bench). With all the pieces cut, I then laid out where the connection screws would go (three in the front half, and two

for the rear). and pulled out the router.

The cross-member connections are a little tricky, since just screwing and gluing these things to the bench top isn't really an option - the top is going to want to expand and contract across its width, so my goal is to try and keep the front edge flush, and have any expansion take place toward the rear. To try and accomplish that, the front-most screw for each cross-member is installed with a straight hole and a little glue, but the other screws are installed through elongated holes with no glue and the special Veritas® expansion washers. To make the holes for these, I started with the 3/16-inch upcut spiral bit and cut all the slots on the exit side of the cross-members first. I then switched to the special Veritas® screw slot router bit, and cut the 1/2-inch diameter counter sunk slots for the head side of the screws. I then relieved the edges of the bottoms of the cross-members with the chamfer bit, sanded them a little to ease any sharp bits, and installed the cross-members with just the one front screw and a little glue on the first 2-inches or so. Once the glue is dried for these things, I think it'll finally be time to get the bench into the wood shop before attempting to get any more work done on it.

Completing the Bench Assembly: late-Summer 2015

I spent a few days working on getting the shop ready for the new bench by taking apart the old sawhorse lumber-stack / bench mess, then making a new

wood storage rack along the wall so I would have a good open area to locate the new bench. I then partially dis-assembled the bench (I kept most of

the base unit bolted together), and re-located the whole thing into the wood shop. After a lot of shimming under three of the legs to account for the

very uneven floor surface, I was ready to get back to building the rest of the bench.

With the bench in the shop, I next got to work on the rear section of the top laminate. I first did some measuring to make the appropriate cut-outs in the bottom Spruce piece to fit around the tops of the leg assemblies, then coated both pieces with plenty of Titebond® II Extend Wood Glue with a roller and clamped everything together. It was sure nice working on the partially built bench - nice and solid with plenty of area to work!

After the glue cured I then set aside the rear half of the top and laid out all the dog and holdfast holes for the front half of the top. I figured it would be a lot more convenient to get all these holes started with the plunge router while the two bench halves were separate so I could get at the edges of each half with the router guide fence. I carefully measured the hole locations according to the plan sheet above, then started each hole with the 3/4-inch auger bit, and followed that with 3/4-inch upcut spiral bit in the plunge router. Once all the holes were plunged for the front half, I then put the rear half on the bench and did the same thing to get all those holes made. With all the holes in place, I was finally ready to get the two halves of the bench top put together.

Putting the two halves of the bench top together was fairly easy - I assembled the thing upside-down on the bench frame with just a dab of glue on each of the cross-members (that were already attached to the front half), and placed a bunch of short pieces of 5/4 lumber between the two halves to ensure I'd have plenty of room between the two halves for the center planing stop / filler strip that gets installed later. With the 5/4 spacers in place, I did a good bit of clamping to keep the two halves in line, as well as a few clamps between the top pieces and the base assembly to make the thing flat. With everything clamped in place, I drove the 2-1/2 inch long screws through the cross-members (that extra work time provided by the Titebond® II Extend sure is nice), and the top was assembled. After the glue cured, I then trimmed the ends flush and cleaned off the screw plugs along the bottom, and applied a couple coats of stain to everything before I flipped it over and bolted it into position. See the photos above right for details. With the top bolted in place, I then spent an hour or so with the No. 6 Stanley plane and flattened the whole thing, then followed that with a few coats of stain and oil finish. With that, the bench base was completed!

Workholding Fixtures & Vises

The bench base and top was assembled, however the bench wasn't ready for use yet, as I still had many workholding fixtures to create as well as get the vise chops made so I could hold my workpieces. I also still needed to make the bottom shelf pieces and tool storage unit. Still plenty to do...

The Center Planing Stop Strip: early-Fall 2015

I actually need to backtrack a little regarding how I put the bench together now, since I made the center planing stop strip prior to applying

the finish to the assembled bench. I wanted to get the top of the center strip planed even with the bench top while I was flattening the top,

and that had to happen before getting finish applied. The center stop was a little complicated as well, since rather than making the typical

strip with notches in it for the cross-members that I flipped over when I wanted to transverse plane some stock, I decided to make something that

I could set at various heights depending upon the thickness of the stock on which I intend to work. This required a good deal of planning to

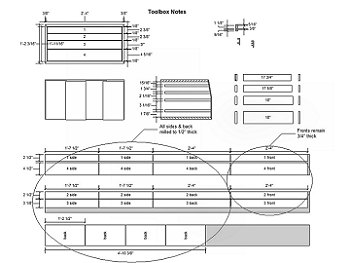

come up with something that would work and wasn't too difficult to make (see the plan sheet at right for details).

I figured the easiest way to accomplish this would be to create a plain insert of the same width for the entire length (except of for the ends), then add a series of small stepped blocks that would allow me to raise the strip to a variety of heights and have those steps rest on the cross-members. I also wanted the center strip to have some slots at the ends to serve as a place to insert a marking gauge, chisel, or saw, and also not have the center strip stick out the ends of the bench when using it for transverse planing. I decided to make the end pieces (from each leg assembly outward to the ends of the bench) separate from the center planing stop and use those as slotted tool storage. The left end piece needed to be stepped as well, so the center piece would rest on it when in use. That also meant I needed a small filler block at the junction between the center and left end. As I said, a little complicated, but it seems to have worked our pretty well.

To make the stepped blocks, I cross-cut the step depths into a couple pieces of scrap two by six, then milled out the step with the router. Once the steps were formed, I then sliced the stock into 1-inch wide blocks. This method ensured all the steps were the same depth (about 3/16 inch). The steps were then glued to the main strip with the strip in place in the slot, and each step butted up against a cross-member. For the two end pieces, I planed some stock down to 1/2-inch thick and 1/4-inch thick, then sandwiched the 1/2-inch pieces between the 1/4-inch pieces to make the tool slots. Once the glue for those pieces was dry, I then cut the ends to the proper profile. With all the pieces assembled I sanded the sides and bottom a little, then placed everything into the bench and planed the top flush with the bench top. The completed piece can be set at 3/16-inch, 3/8-inch, and 7/16-inch heights for working with 1/4-inch, 1/2-inch, or 3/4-inch stock. See the photos at left for more details.

Bench Top Planing Stops & Dowel Former

In addition to the center planing stop strip, I also had a few

other chores to attend to before applying finish to the bench top. I had already done much of the work for the installation of the planing block

in the left end of the bench, however I had planned to have that block align with a small Lee Valley pop-up bench stop to facilitate working

on large panels. I also had a Veritas® Dowel Former that I thought would work well down at the left end of the bench.

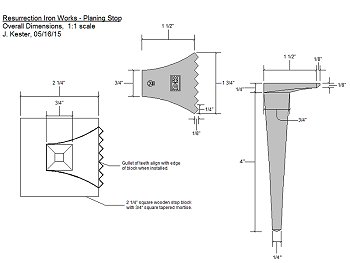

The first item I addressed was the planing stop block. I had contacted a number of blacksmiths back in May to determine who was willing and

able to create the toothed planing stop I was looking to install. Based on the bloggers recommendations below, I first tried Peter Ross, but he never responded.

I also tried Mark Atchison, who eventually responded, but only after a couple months and I already had the stop made by someone else. The guy

that finally came through was Derek Heidemann of Resurrection Iron Works

![]() , in Millbury, Mass. When I contacted him,

he responded immediately. I whipped up a quick plan sheet, and he delivered the item less than a week after receiving the plans. How these

guys can make stuff this nice for $65, I'll never know, but thank you Derek! After having the thing kicking around for many months, I was

ready to install it at last.

, in Millbury, Mass. When I contacted him,

he responded immediately. I whipped up a quick plan sheet, and he delivered the item less than a week after receiving the plans. How these

guys can make stuff this nice for $65, I'll never know, but thank you Derek! After having the thing kicking around for many months, I was

ready to install it at last.

The traditional method of fitting the planing stop block into the bench is to create a large mortise then friction fit the block into the hole. Because my bench is basically stored outside, I wanted to have a little better control over how the block fits, rather than have it too tight in the humid Summer, then just fall out of the bench in the dry Winter. The hole in the bench top is cut slightly oversize to ensure the block will fit (addressed above in the Assembling the Front Laminate photos), but below the bench top where the mortise extends through the front apron, I added a block to the back of the apron with the other half of the mortise that's attached with screws and leather lined. This block allows me to adjust the fit of the stop block as needed, and the leather lining holds the block in place while still allowing easy depth adjustment. I also dealt with the concern regarding the teeth of the planing stop sitting above the bench all the time by making it so I can simply pull the block up out of the bench, then flip it over and insert it from the bottom to store it with the toothed bit under the bench. As usual, please see the photos above right for more details of the planing stop installation.

Tail Vise Assembly: Fall 2015

I discussed most of the tail vise jaw construction above in the

Tail Vise Jaw construction section, however I had only done enough work to get the tail vise frame fitted with the

front apron and bench top. With the bench top now installed (but again, before I actually applied the finish), I needed to add the top piece

to the tail vise jaw so I could plane it flush with the bench top before applying the finish to both the top and the tail vise jaw. The top piece

was cut slightly oversize, then simply glued into position with lots of clamps and glue. After the glue was set, I then cleaned up all the edges

using a flush trim router bit on the end grain, and a hand plane on the sides (see photos at left). With the tail vise jaw sized, it was then fit

into the bench and I planed the top even with the bench top.

Now I needed to get this pipe vise mechanism working by tuning the jaw fit, and I could finally get some finish applied to the whole thing. Easier said than done... while I'm satisfied with the pipe vise function, getting the thing to work as I wanted turned out to be a bit more involved than I would have liked. If I had to do it again, I think I would have just installed a Veritas® Quick Release Tail Vise and been done with it. Sure, it's $300, but considering the time I've been fiddling with this pipe vise thing, I'd have been okay with that. The first problem I faced was getting the thing to open... my original plan was that I could just turn the handle to open it a few inches, then reach inside to depress the release button and slide it out to whatever distance I wanted. The trouble was that the pipe vise base grabs the pipe such that it only prevents it from coming out of the bench, but not from sliding into the bench. So, when I turned the end handle, rather than opening the vise, it simply pushes the pipe the handle is attached to further into the bench. It became clear why they had designed the thing with the ability to add a foot pedal, and that I was going to need to add one to get the thing to work.

I dug through the scrap heap and found a couple pieces of stock that would work for the pedal mechanism, and after a visit to the local hardware store I came up with a small chain and a couple of pulley sheaves that I installed to guide the chain from the vise base down to where I decided to place the pedal (rope stretches - chain doesn't). I had an old metal "Stud Step" thing kicking around, so after a little time with the Sawzall and grinder, I'd fabricated a respectable looking pedal mechanism. I installed the unit below the shelf supports on the stretchers, and it worked out that the chain will clear the tool box without difficulty, routed down behind the right leg. The tail vise jaw still sticks during some of its travel so a little more light planing will be needed, but it seems to be working well enough. After finish application, I also installed the six Veritas® Prairie Dogs in the jaw dog holes, which work very well while staying in place to prevent debris from collecting in those blind dog holes.

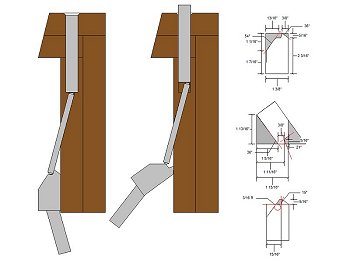

Leg Vise Assembly: Late Fall 2015

The leg vise chop was cut from a hefty chunk of Poplar,

based on plan shown above. I decided to keep the outline simple to match the rest of the appearance of the bench, rather than add the curved outline

that seems so popular on many benches being built these days. Cutting the chop was nothing special, although I did clamp it to the bench and trace

the outline of the leg to ensure everything would line up, rather than try and measure it based on the plans.

One issue I had to deal with was that I had a 36-inch piece of 10/4 Poplar to work from, and because of the 20° angle of the leg, that wasn't going to be long enough. The good news is that because I would be adding a small block to the bottom to meet the length requirement, I could cut the mortise for the parallel guide on the band saw, rather than have to chop the thing out with a chisel. Once the outline for the main part of the chop was cut, I then did some clean up on it, and clamped it back to the bench to mark the mortise location for the parallel guide. With the mortise outline marked, I then got to work on the parallel guide. Rather than cut the mortise for the guide in the chop now, I wanted to get the tenon cut in the guide bar so I could use it accurately mark the size to the mortise from the tenon based on the marked mortise location, rather than try to measure it.

The parallel guide was made from two pieces of 1/2-inch Poplar laminated together, then planed down to 3/4-inch thick. I hoped by using a couple pieces of thin, laminated stock, I could counteract any warp or twist that might develop later, and also reduce the likelihood of the thing splitting under the tremendous pressure that's put on the guide bar holes when in use. With the parallel guide stock planed smooth and nicely fit to the mortise of the leg, I then marked it to length (leaving about 1/2-inch extra length for the tenon through the vise chop), and cut the tenon in the end using a chisel to mark the shoulders and the Stanley No. 71 router plane to clean up the cheeks. I was only taking off 1/16-inch per face, so this went very quickly with the No. 71. I could now trace the tenon onto the main piece of the vise chop, and cut the top half of the mortise with the band saw. I then cut the bottom half of the mortise into the vise chop extension piece, screwed the two pieces together and did a little chisel clean-up for a snug fit. I then re-assembled the chop with screws and plenty of glue. The next day I then trimmed the bottom of the chop to shape and did some final clean-up with the smoothing plane. The next step was to get the screw handle mounted.

Leg Vise Screw Installation

With the leg vise chop and parallel guide ready for assembly, I began

working on the leg vise screw installation. I wanted to get the screw in place and working properly before gluing in the parallel guide, since the

whole leg vise thing would bind up and be a mess if it wasn't aligned properly with the parallel guide.